Your smartwatch talks a lot but may not say much about your health. Constant data collection from wearables claims to improve medicine at large. Is the ‘quantified self’ the next step for patients or is it just a gimmick? Does healthcare improve when doctors access your live data on a whim? After today’s episode, you’ll learn to trust your wearables at the right time rather than all the time.

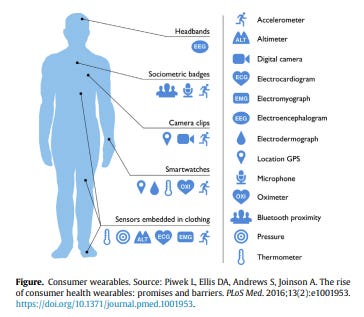

Imagine your sleep and heart data beamed straight to your medical record. Your care team might notice a red flag, then schedule a virtual appointment right away. Our nifty wearables can make that happen. Healthcare wearables, meaning tech that you can put on like clothes, are used for both medical and general wellness purposes. Apple watches can take your heart rate and track exercise goals but can’t time your insulin like a continuous glucose monitor does. Patients can miss that nuance because technology is blurring the line between wellness and medicine. Regulators like the FDA pay close attention. For the purposes of this episode, I’m focusing on the consumer-facing side of wearables, not higher-end devices that may get implanted following a doctor’s order. You might see your doctor once to twice a year and get vital info recorded (e.g. height weight, blood pressure). Pro-wearable users argue that smart devices are a complement for the other 363 to 364 days a year when you aren’t seeing the doctor. Smart device sensors generate health data continuously and we take our devices with us everywhere. Doctors and patients can then form custom health and wellness goals from these vectors.

Regardless of whether you have a consumer-grade (e.g. a Fitbit) or medical-grade device (e.g. a glucometer), someone has to work with the data. In most situations, patients and their doctors take a passive approach if wearables are in play. The heart-rate data coming from a chest monitor sends itself to your medical record, and if your provider notices something wrong, new care gets organized. For other measures, patients can report their own data (i.e. active monitoring) to a physician or health system. This is where the use case for wearables loses ground—patients don’t want to put in extra time to enter info. Smart healthcare devices are supposed to draw a better picture of your health automatically. Patients wonder if they have to do anything more than put on a strap or take a sensor-laden pill. Analysts and consultancies think we’re just beginning to grasp all that smart health gadgets have to offer.

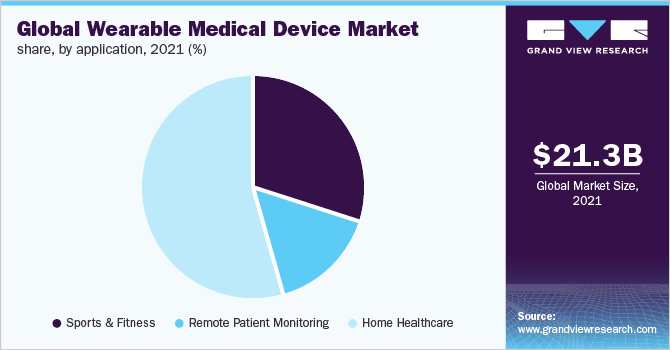

America’s medical wearable market is projected grow at a blistering ~26% per year through 2030. Most of those gains will come from a higher incidence of lifestyle-associated issues like diabetes and hypertension. Serious changes in vitals like blood sugar and pressure make the difference between life and death for such diseases. It’s no surprise that wearables can help providers catch problems early with remote patient monitoring. The overall breakdown of consumer-leaning medical devices also includes fitness and home health. Why is our wrist a popular throne for wearables? The wrist’s skin is thin enough to take a pulse and our arms move enough muscles around to allow for kinetic tracking. It’s also simple to look at your watch between tasks. Sensors are making their way to other places besides our wrists. Headbands and shoes are popular alternatives to stuff a few sensors in. Not to mention that we have supercomputers in our pockets. Cell phones themselves pick up uncountable data (for better or worse) and can have attachments like ECGs to create new tools on the spot. Some vitals are better for wearables than others. According to a survey run by the Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), blood pressure and blood glucose were doctors’ two most preferred statistics from wearables. Though at least half of respondents had a positive view of wearables in medicine, they stated a few concerns every patient should know. The data may be skewed and patients might not be using devices properly. If patients have to enter data themselves for transmitting info to a doctor, that process can give way to potential technical errors. Some people could be wearing their watch upside down. The data could be right on, but the algorithms calling out red flags (e.g. high/low blood sugar or interrupted sleep) can be faulty. Not to mention that companies or bad actors can get a hold of your data to resell. Your doctor might also feel that a bunch of circuits and data intrude on his or her expertise. More research is necessary for everyone to have better confidence in wearables.

When visiting your doctor, there are a few questions worth discussing if you think wearables might help an issue. Is a given product recommended by a physician you trust? Is that device approved by the FDA for some indication? Are there any replicated, peer-reviewed studies demonstrating effectiveness? Even if a smart health device works, the decision-making aspect of the wearable matters. Can the doctor make a medical diagnosis and treatment plan based on a given reading? If so, you have a clinical wearable. Otherwise, your device is a consumer-focused wellness tool. All of that being said, don’t let your wearables control you! It’s easy to overreact to a blip, but reach out to your primary care doctor if there are serious concerns. A wearable’s manufacturer has to spell out what the data tell and don’t tell you—check if a company openly admits vagueness or disclaimers for readouts (e.g. Apple’s “Apple Watch never checks for heart attacks”). Take note of any lengthy privacy policy regarding your collected medical data. In September 2021, the FTC noted that makers of health apps and connected devices have to tell you when there is a data breach.

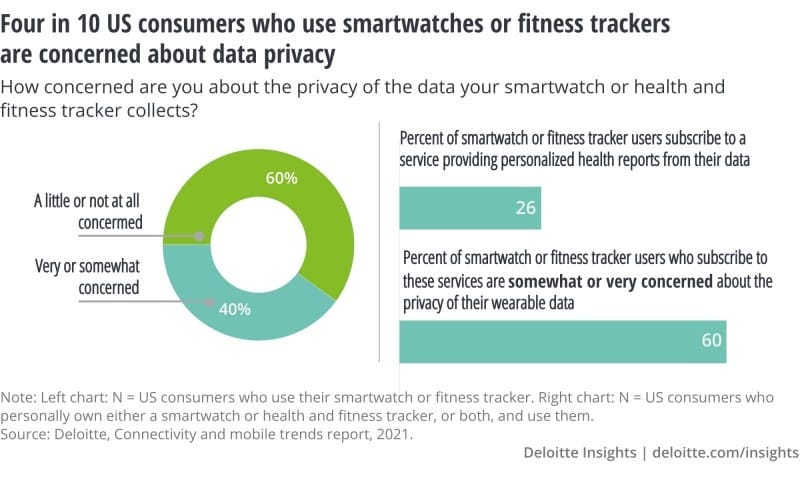

Even if an over-the-counter wearable gives directional advice without any medical leverage, how should we treat our healthcare data properly? The Journal of Nurse Practitioners argues that we’re in the midst of a “quantitative self” movement. In this way, patients feel empowered with data to participate further in their care while allowing providers access the statistical drawing of patients’ health. This sounds cool, but there are tradeoffs we shouldn’t be quick to forget. Wearables themselves don’t create incentives to oversee one’s health—in fact, it’s easy to fall off the grid with following up on your health data if a long enough string of readings look normal. Those benefiting most from wearables (i.e. rural and elderly patients) may not have tech-savviness or access to necessary internet to best use such technology. Overreliance on data and self-diagnosis can also be an issue—you still need a licensed professional to make sure everything you observe checks out. Here’s another worrisome thought: should the insurance and medical industries have greater access to your data, even if you save money or find better health from sharing that info?

According to Deloitte’s Connectivity and Mobile Trends Report survey, four in ten US consumers using smartwatches or fitness trackers are “very” or “somewhat concerned” about their data privacy (in relation to such device usage). The information consent issues stem from data moving to third party companies. Insurers of all kinds can raise your premiums if your medical data suggest a propensity for certain issues. You might get unwanted ads or attention due to health stats implying that you’re sedentary or have a chronic issue. Employers could subvert you from full-time work on the basis of data-driven medical insights. Smartwatches and fitness trackers operate in a gray area not fully accountable to HIPAA. These concerns I rattled off lead to a probable reality for all patients. Of course, the better doctors of tomorrow should embrace technology, including wearables. If you’re unsure if your new phone app or smart headband paints a clear picture, ask your physicians if a given stat or device (e.g. Apple watch ECG, blood pressure sticker, continuous glucose monitor) meets their standards. Wearables do help you accumulate concrete info beyond what’s possible at the doctor’s office, but eventually you’ll need to visit someone for guidance. Even before the pandemic, more Americans have been working remotely or being nomadic in their professions. The next pod will help patients who travel a lot and who believe the world is their office to navigate our medical system across the state lines. Subscribe and stay tuned to Friendly Neighborhood Patient for all the healthcare good stuff. I’ll catch you at the next episode.