Your phone might stick around wherever you go, but your medical care may not follow suit.

When the time comes for you to move to a new state, change jobs, or both, your health plans and doctors would need to change as well. Insurance plans and medicine are (mostly) locked within state lines. Closed-loop healthcare built in the 20th century is part of why our current medical system gets expensive. Yet we live in a connected world where it’s perfectly normal to work from anywhere and move state-to-state like we’re crossing the street. In this pod, I’ll make our fragmented market simpler to understand so you know how to get medical care organized on the go.

Normally I’d start with some history and background of our system, but for today, the practical stuff needs to come first instead. If you’re moving to another state and have a different employer, you probably need to buy new health insurance. You could have the same employer but still need to get new coverage if you have an HMO plan. When you know ahead of time that you need to move to a new state, contacting a local plan broker and checking out the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchange would be a reasonable start. Most people sign up for health plans during a specific ‘open enrollment’ period (usually during the fall), but changing states is considered a ‘qualifying life event’ under ACA rules. You can then buy a health plan outside of normal time frames. Sometimes when changing a job, you’ll need to wait up to 90 days to enroll with the new benefits, even if you secured a plan already. Thankfully, we have short-term health insurance to fill those gaps. Short-term coverage can be as brief as 30 days to pay for emergency and unexpected medical situations while changing traditional plans. I’ll spend more time later on why near-term medical insurance is the market’s best-priced instrument, but there’s something more important to address. What if you live or work in multiple states? It is 2022 after all. When splitting time between states, buy coverage in the place you spend the most time in, or wherever you pay taxes or register to vote. Ask your broker if the available choices offer a national provider network. ACA marketplaces also support a few multi-state plans toting “minimum essential coverage,” but check if you’re getting locked into out-of-network prices beyond the area you spend the most time in.

International travelers should consider their medical insurance as well. Most US health plans won’t be effective or will have severe restrictions abroad. If you frequently hop across the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean, consider supplemental health insurance. This gives you medical coverage for certain trips (but won’t be travel insurance for logistics). Your health might change on a dime whether you like it or not—there may be no choice in seeing a doctor abroad. Reach out to your insurance plan to verify international coverage or member-submitted claim forms, which are filled like an out-of-network claim in the US. The bottom line is this: whether you’re zipping all over the country or the world, a little planning keeps you from getting frazzled with coverage. If you have employer-based insurance, ask your HR team when your plan applies and doesn’t apply across state lines, then make changes accordingly. If you’re taking a marketplace offering, set up the insurance around the place you spend the most time in, even if you’re there 30 seconds longer than a neighboring state across the street.

I’m not the first person to notice that restricting medical insurance usage within state lines makes healthcare a pain.

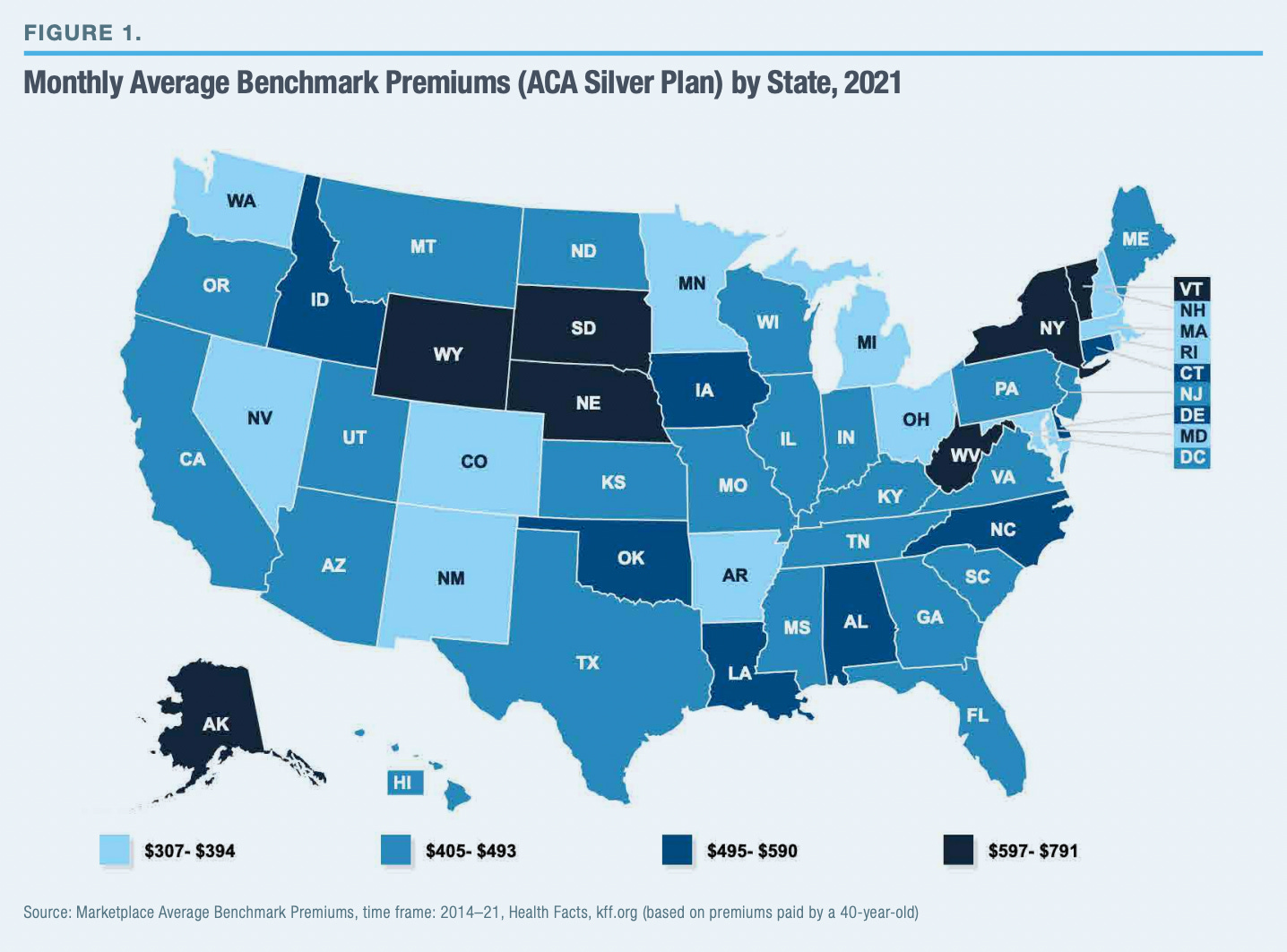

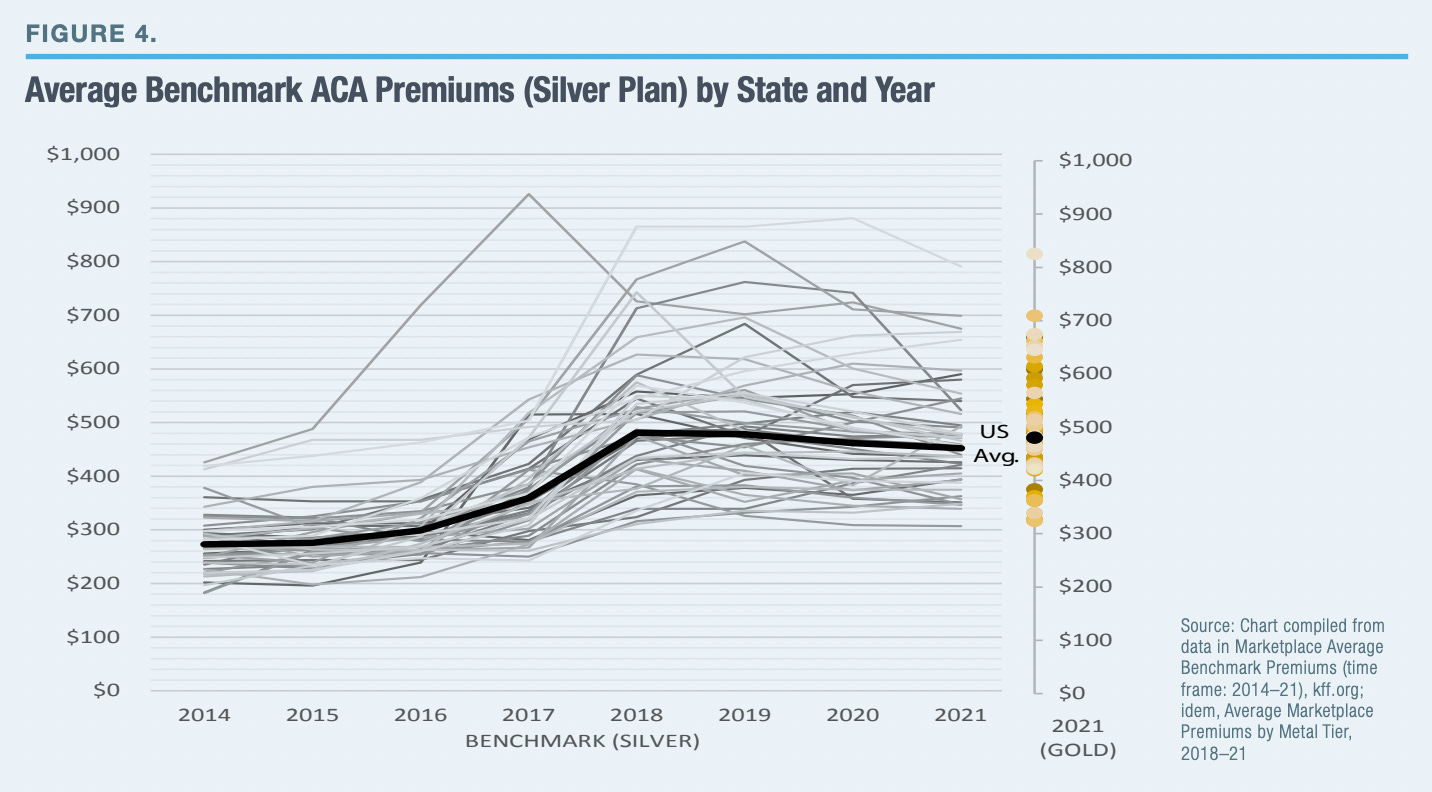

Our constitution’s commerce clause is what makes interstate business happen. The McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945 instead made states the chiefs of insurance regulation. This event brought about fragmentation, reducing competition and giving way to massive differences in monthly premiums (varying by several hundred dollars per month), even at the county level. Let’s walk through a tiny bit of microeconomics 101: the customers (i.e. patients) are captive and can’t substitute a health plan in the next town over without major switching costs. Once states began taking charge of health insurance rules, more physicians and hospitals lobbied over time to raise their payouts (i.e. by increasing benchmark prices) and thus influence higher premiums. State-sponsored individual health plans are also priced according to providers’ and the states’ projected expenses rather than the demographic spread of healthy and unhealthier patients.

The government tried to fix that with the ACA. That didn’t work too well.

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), average individual market premiums available through ACA’s exchange doubled from 2013 to 2017. In 2018, half of US counties had only one plan issuer. The ACA lets states combine their insurance markets so individuals can purchase a plan from any state; however, purchasing insurance from any state is NOT the same as using insurance in any state. Regions with a single plan issuer still heavily control prices, even if you can buy coverage from that issuer wherever. The best-priced health plans in the country are the Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance (STLDI) plans I mentioned earlier, offering wide networks within state lines for limited periods. About half of states have STLDI options, but patients still can’t take such coverage across the border without buying a new plan. As a result, patients don’t often renew their individual or employer health plan when moving. The Manhattan Institute think tank covers even more ground about our state-based coverage system. I’ll link that policy research on my page at rushinagalla.substack.com.

It’s not just insurance that can’t move between states. You’ll need to start from square one with your doctors and pharmacies as well.

The US has national standards for medical training, but each state has its own licensing board. Physicians can only practice medicine in a state they have a license in (though exceptions among some bordering states exist). State licensure, which began in the 19th century, was meant to prevent the random providers from peddling their pseudo-medicine and magic potions in the next state over. With the advent of evidence based-medicine and nationalized training, we don’t have as many quacks. Still, if a doctor’s licensed in one place and wants to practice somewhere else, pretty much every state requires proof of med school completion, a one-time initiation fee, and yearly license fee among other criteria. By design, it’s not fun to keep up multiple state licenses, each of which have their own dues. These restrictions even apply to telemedicine, though with some loosened rules due to the Covid pandemic. Having telemedicine work seamlessly in any state or territory is a reasonable next step for national practice standards. When it comes to drugs, if you notify your pharmacy team about a switch, most staff will transfer your prescriptions without a hassle. Being established with a major retail pharmacy like CVS or Fred Meyer makes the process easier. Again, planning ahead of time when possible is your best friend. Speak with your care team and pharmacists to have your records and prescriptions transferred, and verify that said info made it to the right destination (e.g. another clinic, pharmacy, office). Believe it or not, there are new developments happening that are smoothening our state-locked insurance and medical system.

To put doctors in more places where they’re needed, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) has been considering ‘expedited endorsements.’ This is effectively like having TSA precheck for medical licensure. A more extreme solution would be a national licensing system or wider license reciprocation among states (i.e. like using your driver’s license). I’ll admit that building smarter interstate health plans and medical practice rules are tough asks, but in a vacuum, more choices and appropriate substitutes for a good (i.e. medical care) should cut prices. Water moves to where it isn’t; both medicine and health plans should do the same thing but current rules prevent that transfer from happening. There’s also a massive difference in pricing insurance based on starting with a state’s expenses versus patients’ innate medical and demographic risks. Let’s continue having these discussions to bring about the change we all need. Speaking of need, another massive concern for both patients and the government is how we can save money on drugs. You might have seen cards from both pharma and insurance companies giving prescription discounts. I’ve talked a little about drug pricing in earlier pods, but for the next theme I want to demystify the world of discount and copay cards so you’ll know exactly what to pick for the best savings. Stay tuned and subscribe to Friendly Neighborhood Patient for a little common-sense on healthcare. I’ll catch you at the next episode.