It’s totally normal for people to ask where their food comes from but we don’t always do this for prescription drugs. Every medication has to get from a lab to your pill bottle somehow. Ever since the Covid pandemic and the quick approval of its vaccines, patients became more aware of how modern medicine comes about. Our drug approval system has more nuance than just expensive 10-year challenges and quick 12-month emergencies. Let today’s episode be a simple crash course about how our country approves drugs and the first steps to untangle that messy, twisted process for the better.

We’re going beyond just talking about our country’s main drug regulator: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patients deserve to know every hoop their pill jumps through, and more importantly, doesn’t jump through. This is why you’ve heard a lot of public figures say that a drug or vaccine is “generally safe and effective.” Every marketed prescription and medical device in the US meets that benchmark through formal approval. Here the FDA is supposed to get answers to at least three questions, among many others: is the drug safe, does the drug work, and is the drug accessible?

At the highest level of new drug research, there are two major paths to follow, both of which have massive consequences for patients. Pharma companies big and small can keep developing the greatest medical advancements in the world exceeding all of the FDA’s needs over time, but at a slower pace. Or the standards of approval itself can be changed to bring more drugs to market. The spoiler is that it’s much easier for pharma companies to take the latter option than to develop better innovations. Remember 2006-2008: underwriters preferred to loosen credit standards for subprime borrowers instead of building smarter financial instruments or finding stabler customers. Not every drug manufacturer is predatory, but like anything else in a market economy, incentives can lead to behavior that doesn’t always help consumers. Before we get into why the drug research process is changing for better and worse, every patient should know the absolute basics of what’s called “drug discovery.”

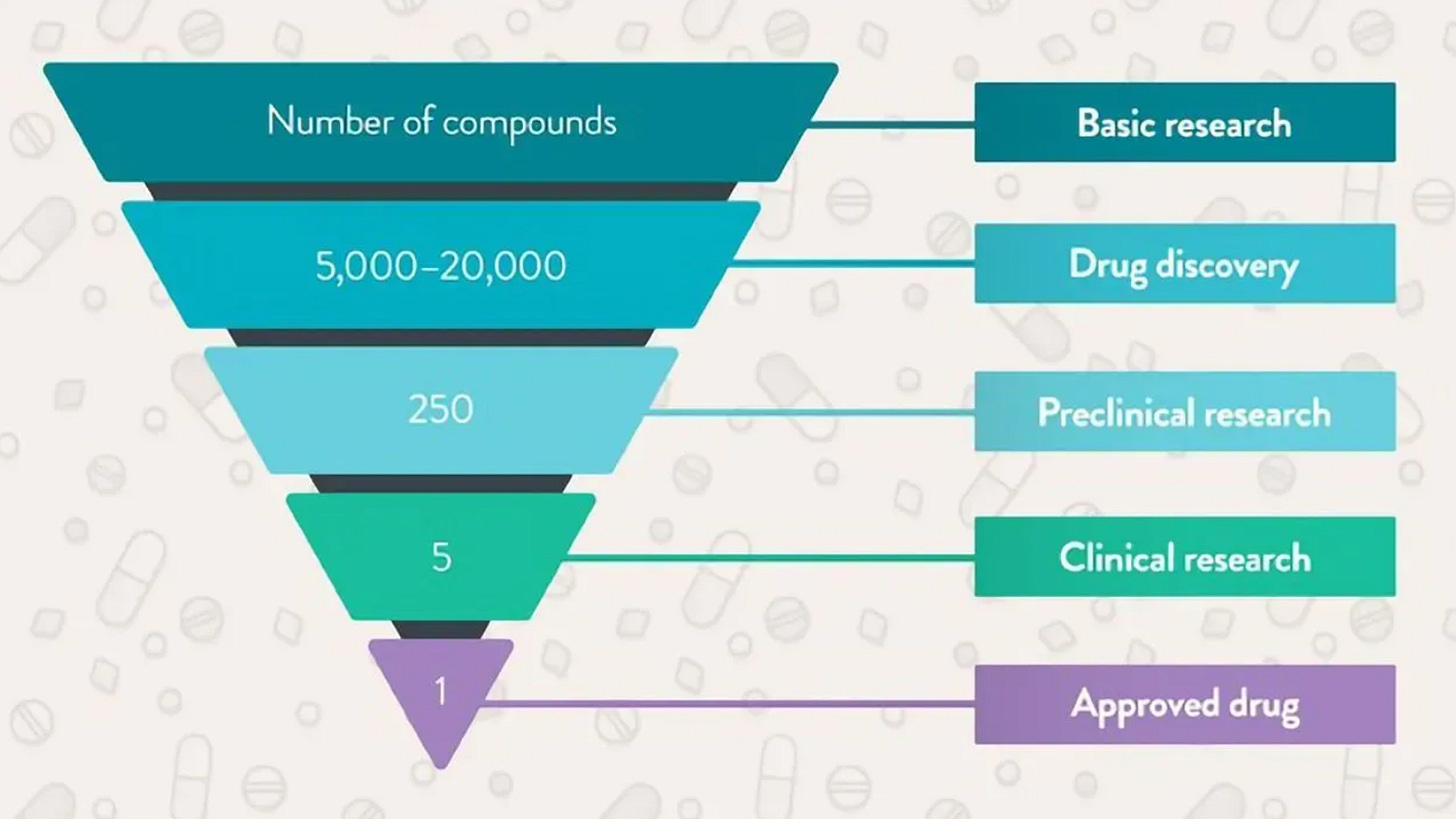

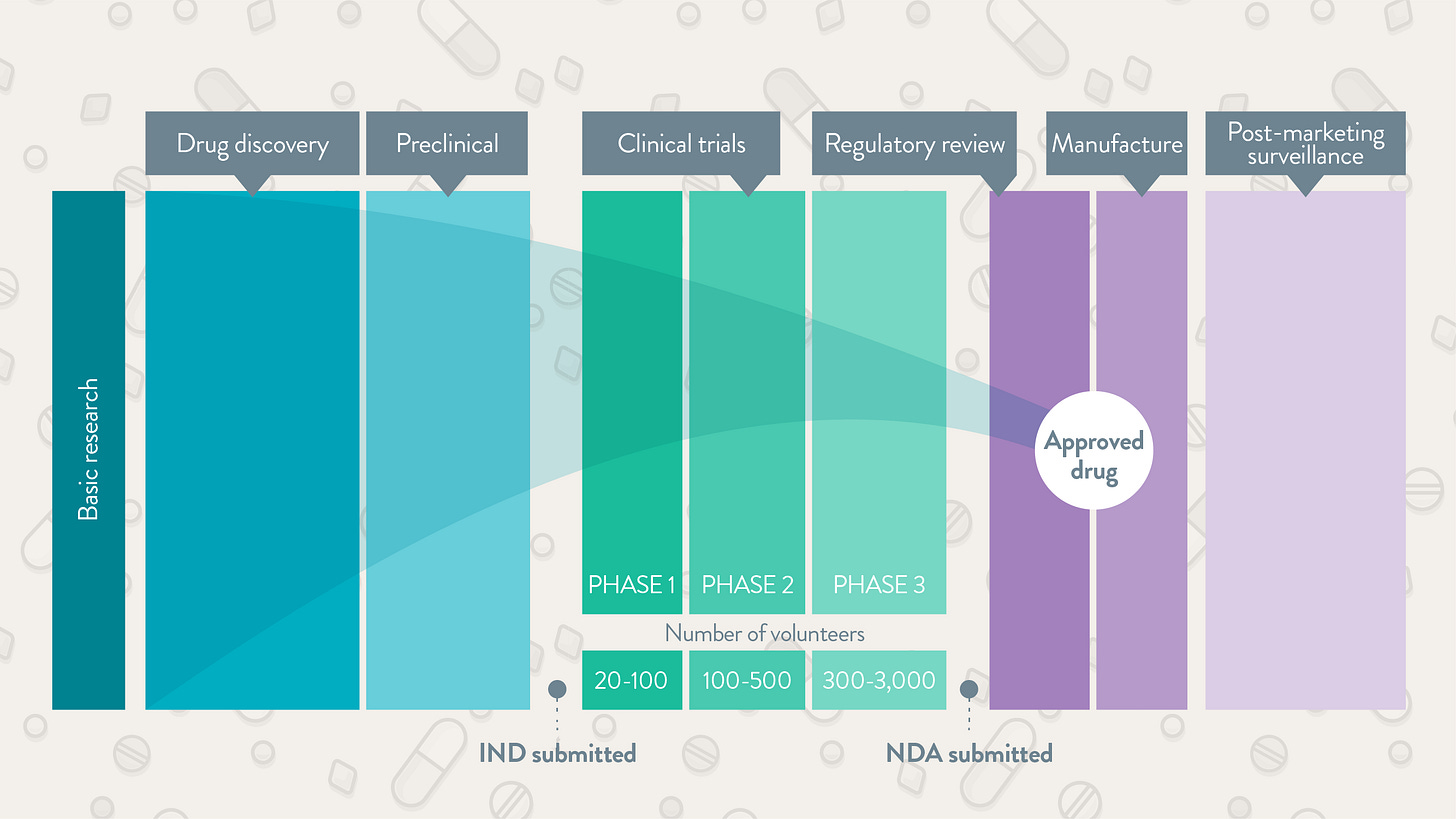

The sheer number of steps in taking a new drug to market is why development takes years. You’ve probably heard of the classic phase one-two-three approach. Before those steps come into play, manufacturers have to figure out if a molecule’s “druggable.” This stage is effectively the research funnel. Hundreds of thousands of combinations need to be filtered by scientists and artificial intelligence. After finding some candidates, the pharma company whips up an outlook for manufacturing, scale, and costs. We’re not yet at phase one. At this time, the candidate drug in question goes through preclinical tests in animals like mice or receptacles like petri dishes. This step addresses the first safety worries. If a new medicine cocktail kills mice, the odds of it working in humans might be dim. At this point the drug company submits an investigational new drug application to the FDA. The requirements here vary depending on factors like the drug’s targeted disease and level of innovation.

Now our drug can move onto phase one. The patient sample begins at a few dozen before including thousands more as the new target reaches phase three. Earlier steps focus more on safety and proper dosage. Later paths deal with efficacy and consequences that only come to light over years. If the data look appropriate, the drug company then fills a new drug application to the FDA. Once the regulator gives the green light after many comments and revisions, the manufacturer scales up their operation, distribution, and marketing. The business isn’t free and clear yet. Just like the Marvel movies, there’s always another phase. Phase four is where a manufacturer oversees many thousands of patients using the new drug in the wild. At this stage, scientists troubleshoot real-world problems that a trial wouldn’t be able to catch. What I just covered is the textbook process for how most drugs arrive on the scene. But what if a drug heals a disease like Alzheimer’s or a severe cancer that has no other alternate medication? What if a medication’s early testing suggests that major benefits are in sight but further studies would take too long? Most drugs still don’t succeed, but these questions are part of why the FDA’s approval process has been faster during the last couple decades.

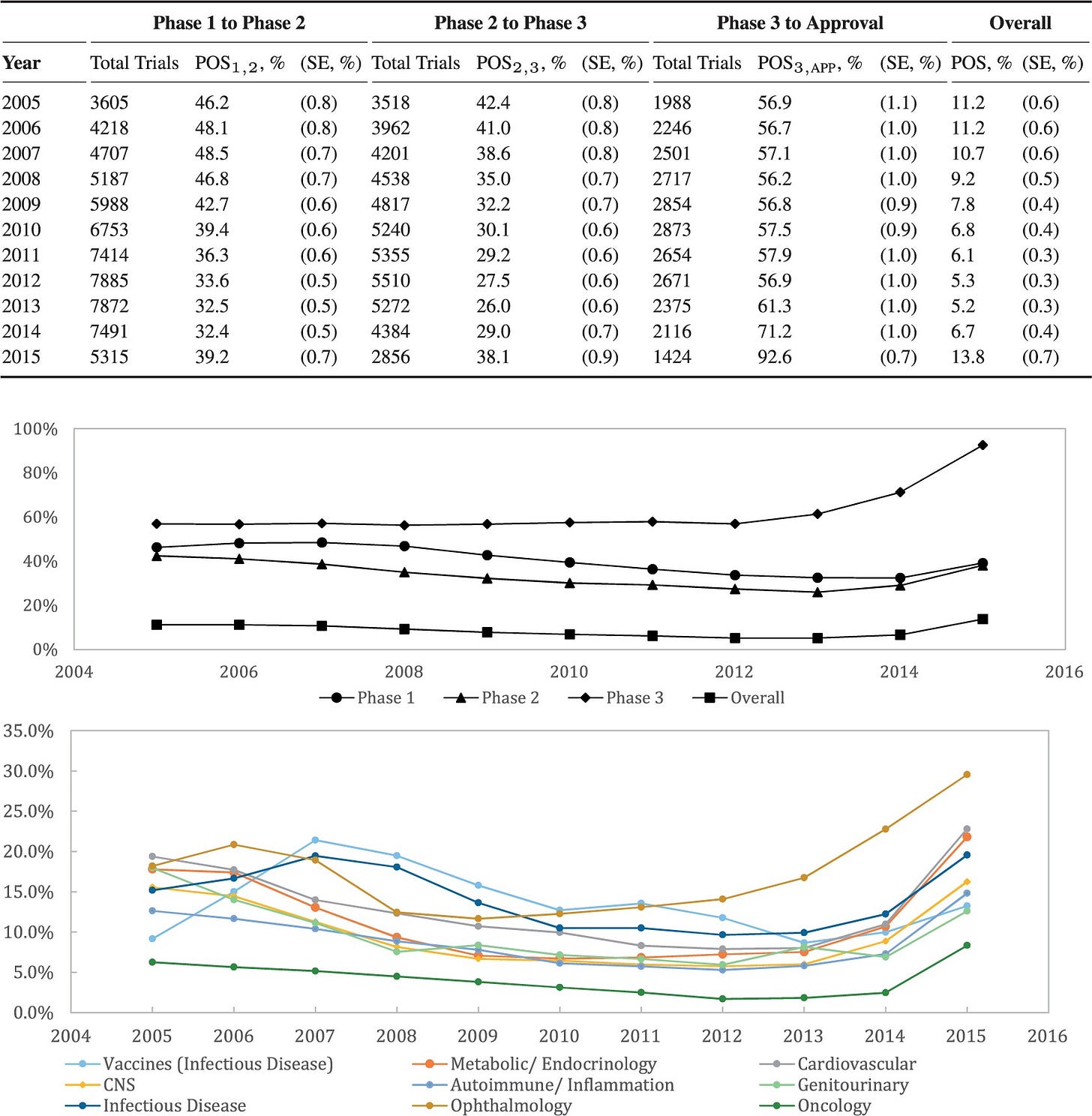

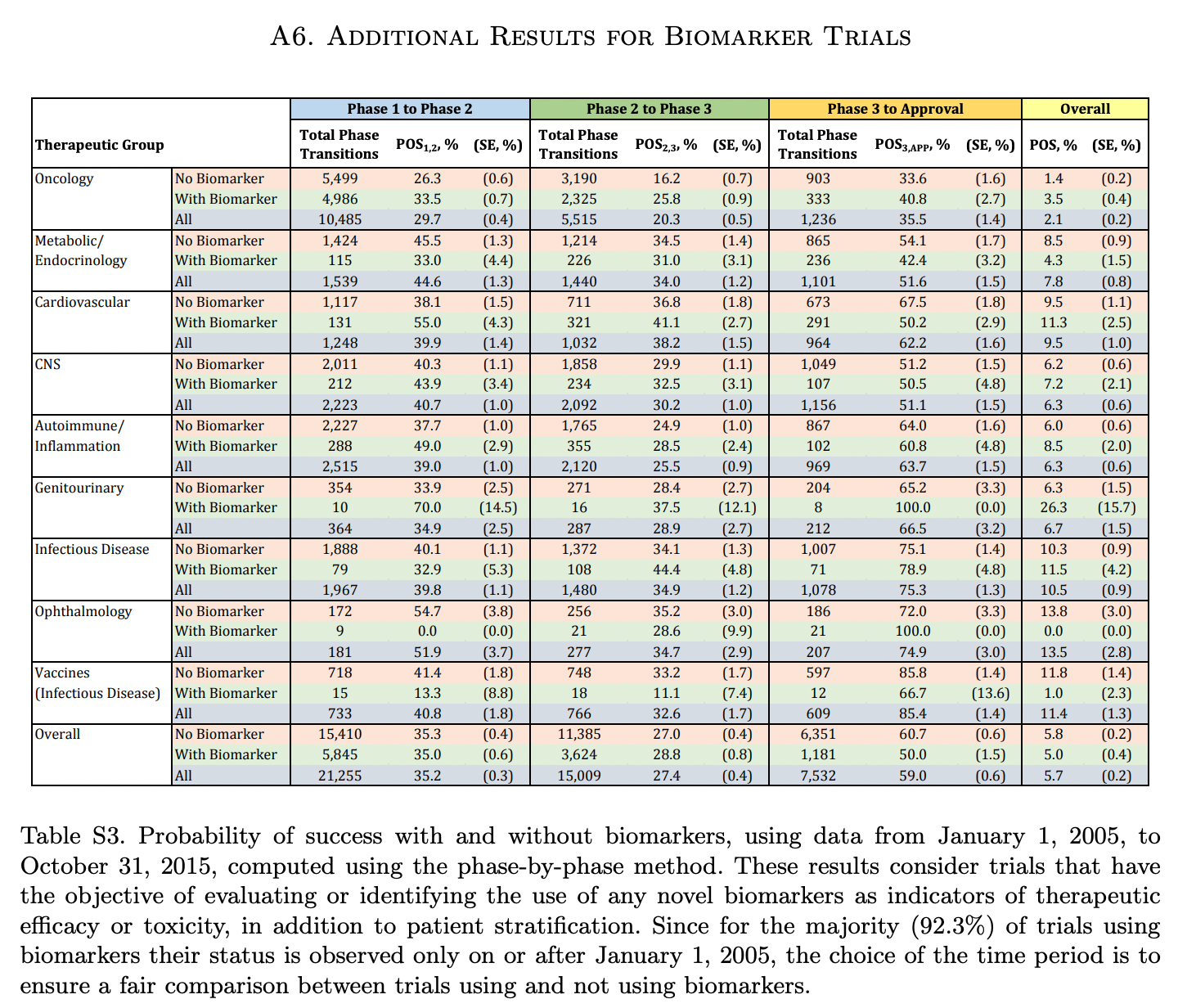

Lawyers at Harvard Medical School’s Program on Regulation, Therapeutics and Law analyzed the FDA’s drug approvals between 1983 and 2018. The authors found the FDA’s median review time for standard applications falling from 2.8 years between 1986 and 1992 to ten months in 2018. The number of average new drug approvals per year increased from 34 in the 1990s to 41 in the 2010s. Since new meds take several years and billions of dollars to hit the market, more novel drugs per year sounds great. After knowing the real drivers of those quicker approvals, that’s not the only conclusion to draw. The triggers start with the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 (making rare-disease targets easier to develop) and the higher incidence of drug companies paying fees to the FDA since then to backstop the agency’s review process. By 2018, industry players’ fees made up ~80% of FDA employee salaries for drug reviews. That regulator also instituted “accelerated approval” in 1992. That designation among others is meant for drugs addressing conditions with no alternatives or drugs being much better than the next best choice. With a traditional approval, pharma companies have to prove their drug can deal a quantifiable net benefit for the patient’s disease. The cancer has to go into remission. The rash has to go away or critical symptoms need to subside. Those benchmarks paired with some appropriate statistic are called endpoints. Ever since the advent of accelerated approval and breakthrough therapies, the FDA’s allowed for surrogate and intermediate endpoints. A surrogate endpoint can be a lab measurement, image, sign, or statistic that suggests a medical benefit but is not actually a medical benefit. Intermediate clinical endpoints may capture some therapeutic effect that should happen on the way to an intended outcome of a drug. A simple example is novel cancer treatment. One might expect that if a given drug puts a cancer into remission, that’s great. Unfortunately, that will take lots of time to figure out using traditional steps. If a drugmaker builds a cancer medication that’s proven to reduce tumor size (but not necessarily put down the cancer for good), the FDA might consider that evidence good enough for quick approval. That measure can be thought of as a reasonable predictor of an effective medicine. We’ve seen the emergency use authorizations in play for the Covid-19 vaccines and antiviral pills. Are faster approvals changing the actual success rates of new drugs?

Institutions like MIT have been tracking drug approvals over time by phase and condition. Success rates are climbing to higher single-digit percentages depending on the disease. A number of market-wide factors are behind that change, but the implementation of surrogate endpoints from special approvals and industry-related fees are the main drivers. Due to these changing incentives, the FDA finds the pharmaceutical industry as the more important party to appease than patients. As a result, around half of newly approved drugs today are based on one pivotal clinical trial instead of the usual two-plus. Developing a new drug remains expensive (ranging between $161M to $4.5B), so quicker successes with the FDA give more bang for the pharma company’s buck. It’s worth asking if the FDA should keep loosening certain drug approvals as long as the post-market phase IV monitoring is appropriate. Or should approved drugs jump through every single regulatory hoop over seven to ten-plus years but have a much higher chance of great efficacy? Regardless, the take-home message is to be aware of where your current drugs came from.

So what can patients do to get informed about prescriptions? Let’s start with the meds you’re taking (but if you’re not on anything, good for you). Drugs@FDA and clinicaltrials.gov are the best sites displaying basic info and possible red flags. There’s plenty of complicated, esoteric medicalese as well, but I can help you find signals among the noise. Aim for concrete items like how the randomized trials were set up and if there are comparisons made between the drug you’re on and alternatives in the space. See if the medication was approved faster than normal (e.g. less than two to three years start to finish) and the reasons why that happened. These resources will get you informed and can help in moments where your doctor’s giving a choice for certain medications. I’ll link those webpages on my post at rushinagalla.substack.com. Take full advantage of online records for the insight to make better decisions. Along those lines, there are a surprising number of public subsidies in healthcare that many large players take advantage of. The upcoming pod covers those basic choices. Stay tuned and subscribe to Friendly Neighborhood Patient for medical field commentary. I’ll catch you at the next episode.