There’s no doubt that our medical system’s expensive to a point of comedic tragedy. No shortage of private and public entities have tried to make medicine cheaper. Ironically, the federal government tries to spend money to save you money in healthcare. Enter the subsidy, an economic instrument both loved and detested by many. Subsidies are used in many parts of the economy, but with medical care in particular, the feds tackle drug development and health insurance among other sectors. Today’s episode tells you why assistance with medical funding makes healthcare both cheaper and pricier for you.

Normally a subsidy involves someone, usually a large player like the government, making something cheaper. Farmers get payments for all kinds of crops if real yields aren’t good enough. Recent laws passed by congress will give money and benefits to semiconductor firms to generate chips with US-based fabricators. However, aid isn’t usually smooth. Unintended consequences (or what economists call ‘externalities’) are part of the game. Some parties uninvolved with federal assistance stand to absorb huge benefits or losses based on where the government’s purse goes next. There are other actions that aren’t necessarily subsidies but indirectly make other parts of a system cheaper due to some change in supply and demand. Healthcare is no different. Patients have to know the benefits and hindrances of the country’s medical funding. The best place to begin is with insurance.

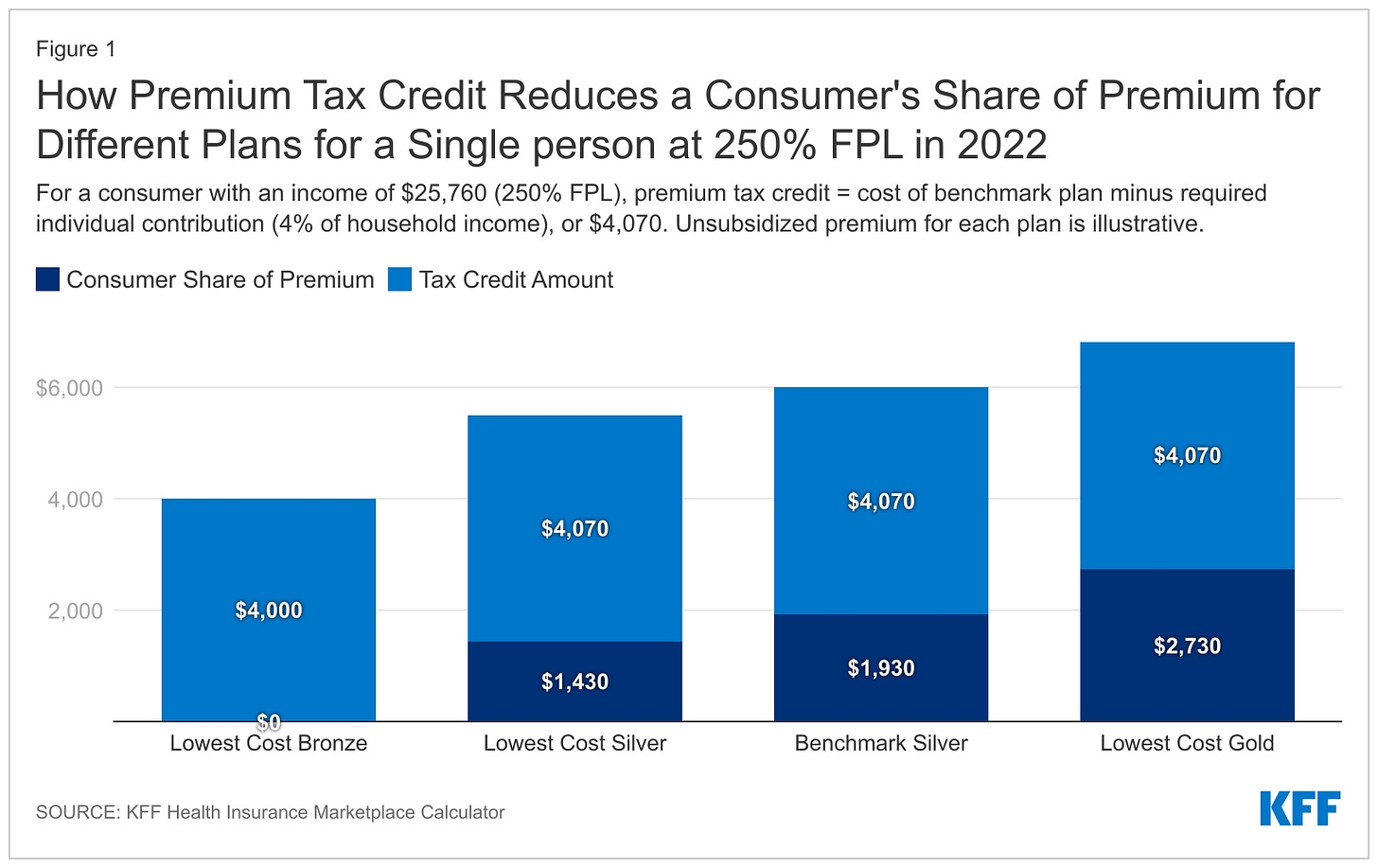

The necessary concept of insurance is having a majority of people with no risk of accidents pay for the minority of people with high risk of accidents. Healthy people, in effect, subsidize the unhealthy. Simple enough. Getting medical coverage is already pricey whether it comes from your employer or an individual marketplace. Here is where the government steps in with the purpose of reducing the number of uninsured Americans. There are two major health plan aid instruments at play: the premium tax credit (PTC) and cost sharing reductions (CSR). Both are linked to medical insurance’s metal-based ranking system. Bronze-tier plans have lower monthly premiums (i.e. the insurance costs you less money to keep) with higher out-of-pocket requirements. Platinum rarity offers higher premiums with less out-of-pocket responsibility. The PTC, hence its name, cuts monthly insurance payments. This policy targets Americans between 100% (~17.4K for two people in 2022) and 400% of the federal poverty line (FPL). The savings work on a sliding scale indexed against the second-lowest silver-tier plan available. The underlying triggers supporting that math are “premium caps.” States determine those limits. For example, your health insurance premiums shouldn’t exceed ~3.5% of income at 138% FPL or 9.86% of income at 300% FPL. The quickest way to guess your PTC is to find the marketplace’s second-lowest silver tier premium and subtract that from the premium cap based on your income. Both of those variables are publicly available. I’ll link the Kaiser Family Foundation’s handy subsidy calculator and data on my page at rushinagalla.substack.com.

Patients can apply to whatever tier of marketplace plan they want and the PTC will adjust. In order to qualify, patients can’t have access to an employer-based plan, even through family, and also can’t be eligible for other public programs like Medicare, Medicaid, or CHIP. Unfortunately, the current rules gave way to what’s called the “family glitch.” You could still qualify for PTC based on income. Yet if a family member can access an employer-based plan that meets premium cap standards at the employee level, yet exceeds the cap at the family plan level, you qualify for nothing. Although the IRS changes FPL benchmarks every year, inflation could push your nominal wage higher and thus cut the real PTC’s benefits. In any case, applicants disclose their personal info on an insurance marketplace before getting a notice about qualifying for the PTC or not. Members can then have the credit paid out at once, claim it during tax time, or some combination thereof. Regardless of what the actual dollar reward is, premiums still need to be paid in full. Families with inconsistent cash flow may not be able to keep up.

The other major components of health plan assistance are CSRs. Such benefits apply to out-of-pocket obligations (e.g. high deductibles, copays, and coinsurance). To get this, patients need to qualify for PTC but also stay in a tighter FPL band of 100% to 250%. Members also can only use CSR for silver-tier plans. That sounds limiting, but the government also imposes out-of-pocket maximums for any marketplace offering even if PTC or CSR remain active. Currently the out-of-pocket max is $8700 for singles and $17,400 for a family, but those required spending levels do fall if cost sharing applies. Health plan aid impacts personal tax returns as well. If you have insurance through work, your employer’s contribution to the health plan could be deducted from taxable income at the paycheck level. As I’ve mentioned on this publication before, I’m not a lawyer or a CPA, so definitely consult your counsel for specific advice. Considering how much money could be at stake, you should go and get the best opinion on the matter.

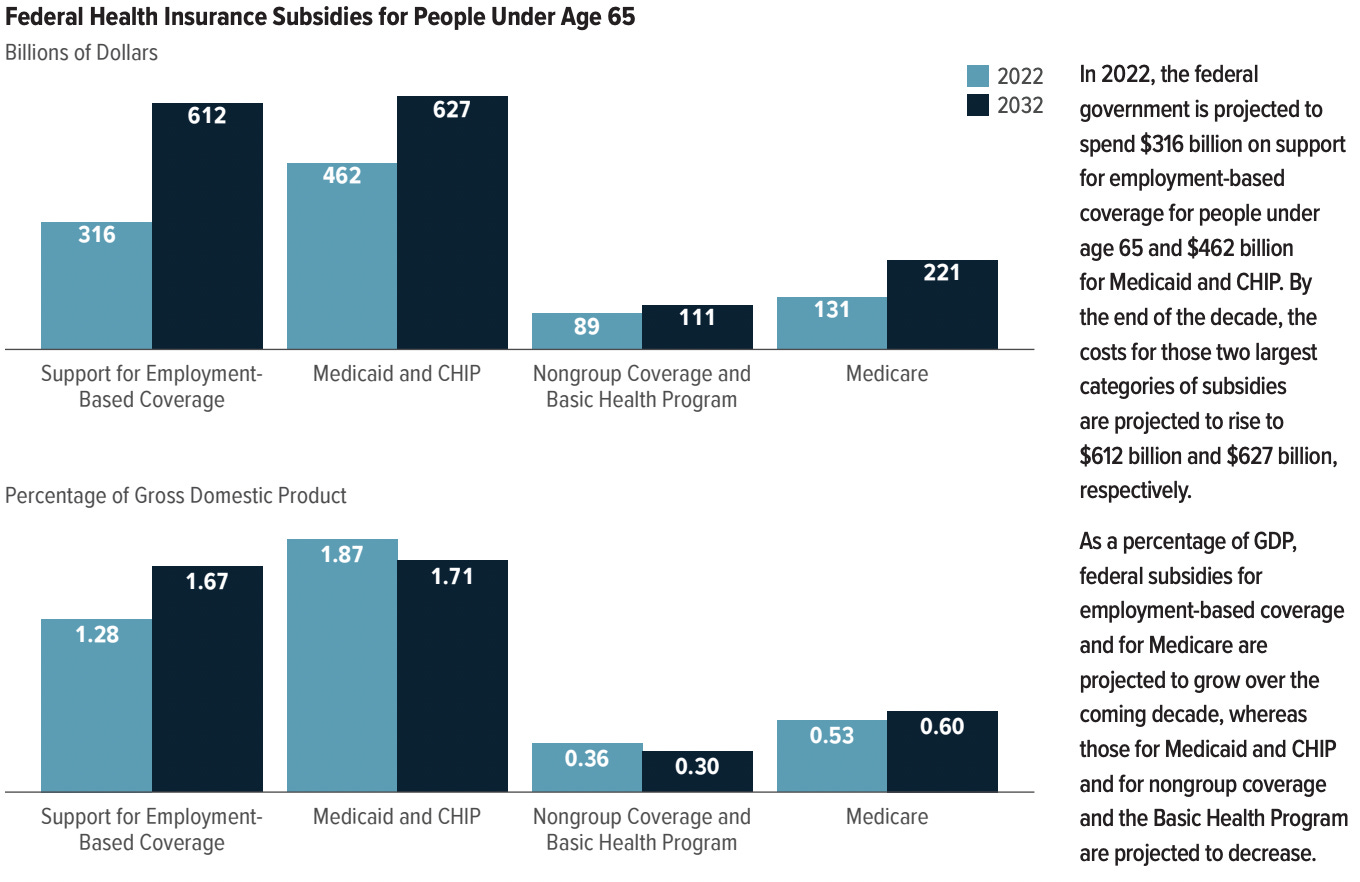

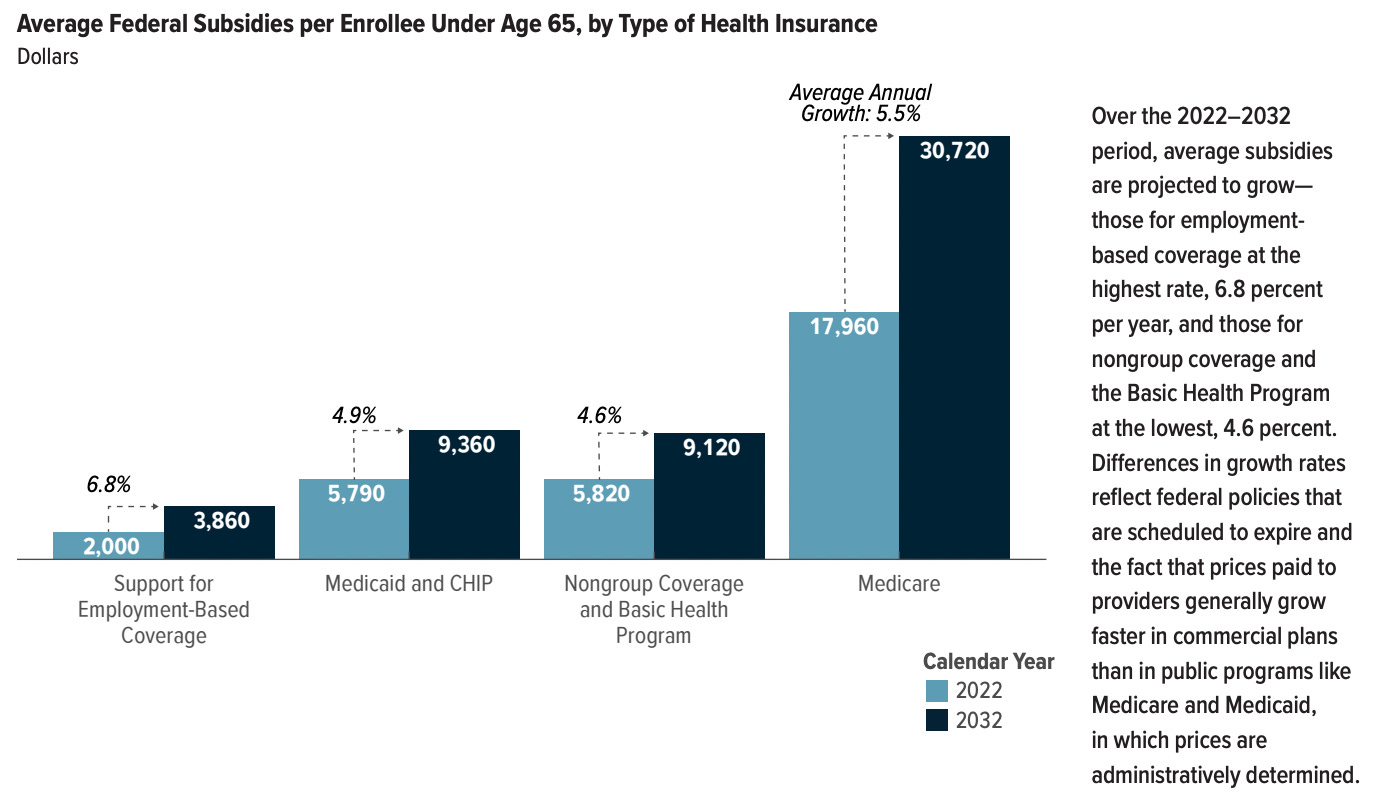

Money for medical coverage assistance has to come from somewhere. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the government spending ~$997B in net subsidies for insured people under 65 years old. That’s 4% of GDP. From the largest to smallest share of that money, the government backstops Medicaid and children’s health insurance (42% of $997B), employment-based coverage breaks (37%), Medicare enrollees under 65 (14%), and then ACA plan subsidies (7%). The CBO also projects the average subsidies per enrollee to grow ~4.6%-6.8% per year through 2032 when total net assistance could tally $1.6T. As long as the government is subsidizing health coverage through direct funding and tax credits, then at some point, taxpayers need to fill up the shortfalls. Higher taxes to Uncle Sam or higher premiums to insurance companies would be the next effects in that cycle. The blessings and conundrums of subsidies extend beyond health plans.

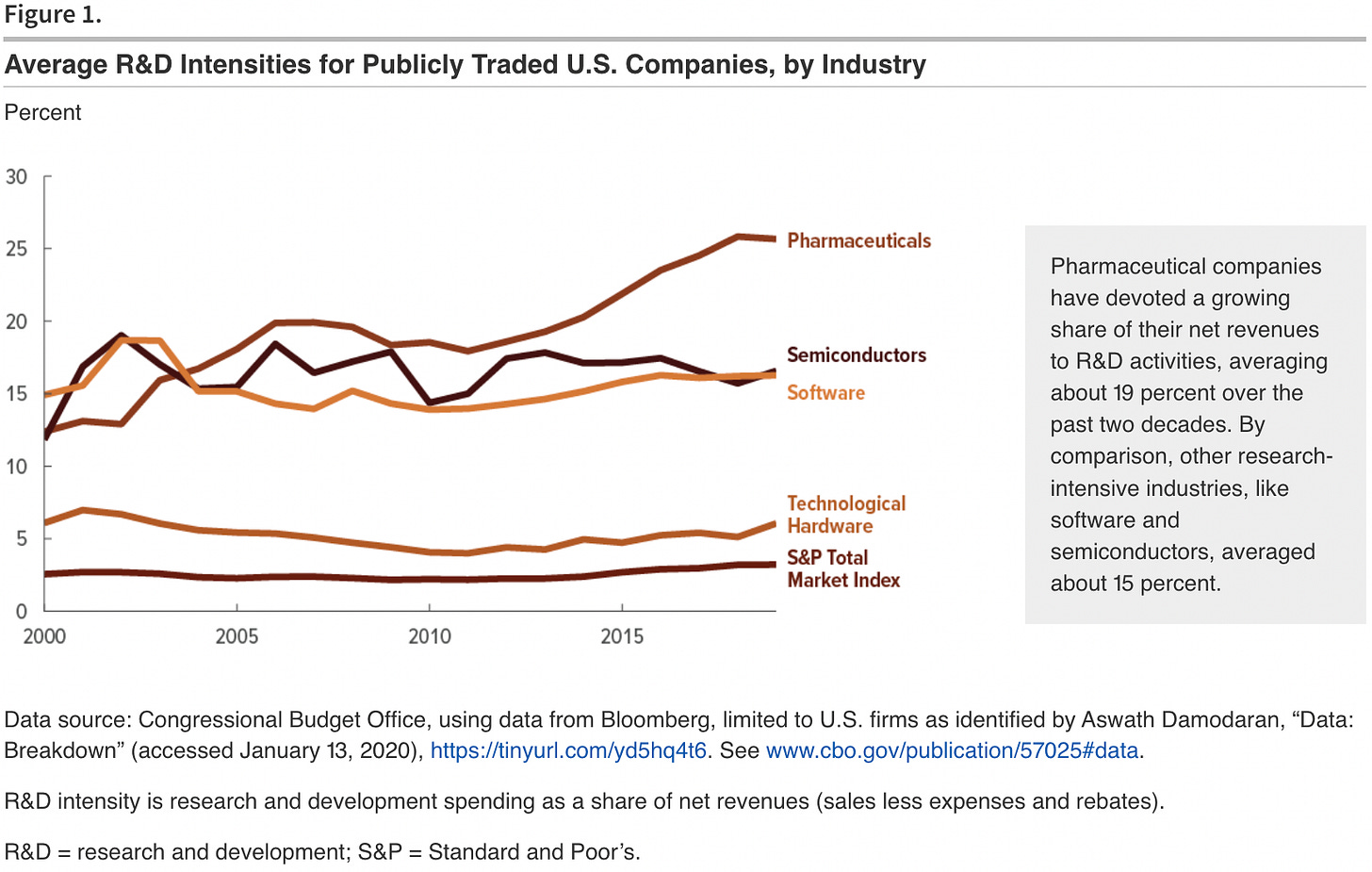

More government interventions in healthcare apply to prescription drugs and biomedical research. Medicare and Medicaid drug coverage can tip the scales of pharmaceutical demand on a whim. Either program could decide one year to reimburse popular drugs like Humira or Eliquis at a 10% lower price. Any drug-maker would become uninterested to innovate upon those fields of drugs. The US also influences pharmaceutical supply via direct funding and tax benefits for R&D. New meds already require massive time and money to come into existence. The government’s research tax credits and expense deductions make the multi-year development somewhat more tolerable for manufacturers. Basic research by the government is necessary in giving way to new medicines. Private firms won’t believe they’ll benefit from new biological knowledge without their competition creating products in a given field at the same time. This is part of why there’s a complementary relationship between the National Institute of Health’s funding and private R&D investment (i.e. more NIH funds correlate to more private drugs in the pipeline). Recent and simple examples show these aims in action. Operation Warp Speed involved the US agreeing to put up R&D money for the Covid-19 vaccines. On top of that, America guaranteed money at the other end of the pipeline in agreeing to buy many doses of the vaccines. In this scenario, the government calculated the vaccines’ expected value to society probably exceeding the magnitude of subsidies. Those policies combined with Pfizer and Moderna’s thirst for another juicy, profitable market are why our country had the vaccines in one year rather than ten years. A recent law elsewhere demonstrates a negative externality in the world of healthcare subsidies.

The new Inflation Reduction Act’s rules around Medicare “negotiating” prescription drug prices would likely cut future drug revenue expectations and in turn make pharma R&D more expensive in relative terms. That legislation allows for excise taxes of 95% on select medications over time if drug-makers can’t agree on a price Medicare chooses. Such punitive measures could incentivize manufacturers to avoid creating high-need, mass-market drugs for diseases like diabetes and obesity. Patients have to be vigilant about these consequences that could make a routine drug refill damaging to savings.

Because of our country’s healthcare spending in order to save patients money at the medical insurance level, more patients will keep enrolling in these federal and local subsidies. Generally speaking, if your income is below 400% FPL, health plan assistance eligibility is a possibility, and if you’re making more than 400% FPL, you’re probably funding some of other people’s benefits. Keep an open mind about who’s footing the healthcare bill, even it’s a matter where you don’t open your pocketbook immediately. Choose your elected officials carefully with regard to both freedom and your health. Private companies and public corporations have been making their own forays into healthcare at large. Any firm aims to both save money and make money—hospitals and clinics just happen to be attractive spaces at the moment. The upcoming pod covers why major companies are buying medical practices and how those moves affect everyone’s communities. Stay tuned and subscribe to Friendly Neighborhood Patient for all the healthcare narratives you need. I’ll catch you at the next episode.