You might look out to the ocean and see the tiny lip of what becomes a massive wave by the time it hits the shore. In the world of healthcare, that phenomenon would be like investors buying up hospitals and clinics of all kinds. Corporations are joining the fray as well—they, like anyone else, want to cut their medical expenses. Mainstream press focuses on the “greedy corporate overlord” narrative whenever a non-medical business buys a clinic. Under this theme, such moves could be anticompetitive and kill the care patients get. There’s some truth to those outcomes. Yet the reality of investor-owned medical offices is nuanced. There are more layers to ownership-based incentives now than ever before. This episode’s here to tell you why someone buying a clinic brings massive consequences for patients everywhere.

Consolidation is the favorite word of every healthcare investor, economist, and pundit. You’ll find it happening with pharmacy-owned retail clinics, investor-owned hospitals, corporate-owned clinics, and insurer-owned health systems. The days of every local clinic being owned by doctors are long gone. I’ve mentioned in a previous episode that a little over half of physicians are employed by or partner with a hospital, health system, or corporation (per the American Medical Association’s most recent biennial survey of physicians in Fall 2020). You’ve also probably heard of Amazon’s recent deal to buy the firm behind the primary care chain One Medical for $4B. That acquisition brings Amazon ~200 domestic clinics and 770K patients. Now the company can weave that with its existing telemedicine and prescription delivery services. The value prop to Amazon is simple: if they control their employees’ healthcare choices and funding, the corporation saves millions if not billions on long-term medical costs. Amazon’s staff, who are then patients, consult with Amazon doctors who then contact Amazon pharmacists who then use the company’s vast logistics network to deliver meds on time. All these expenses would then be insured by Amazon itself or in partnership with a major health plan. Other firms could then buy into this corporate-owned, regional (or even nationwide) healthcare system cutting medical costs for their staff. Because of this, public companies like Apple, Tesla, and Intel have been setting up their own clinics at the workplace.

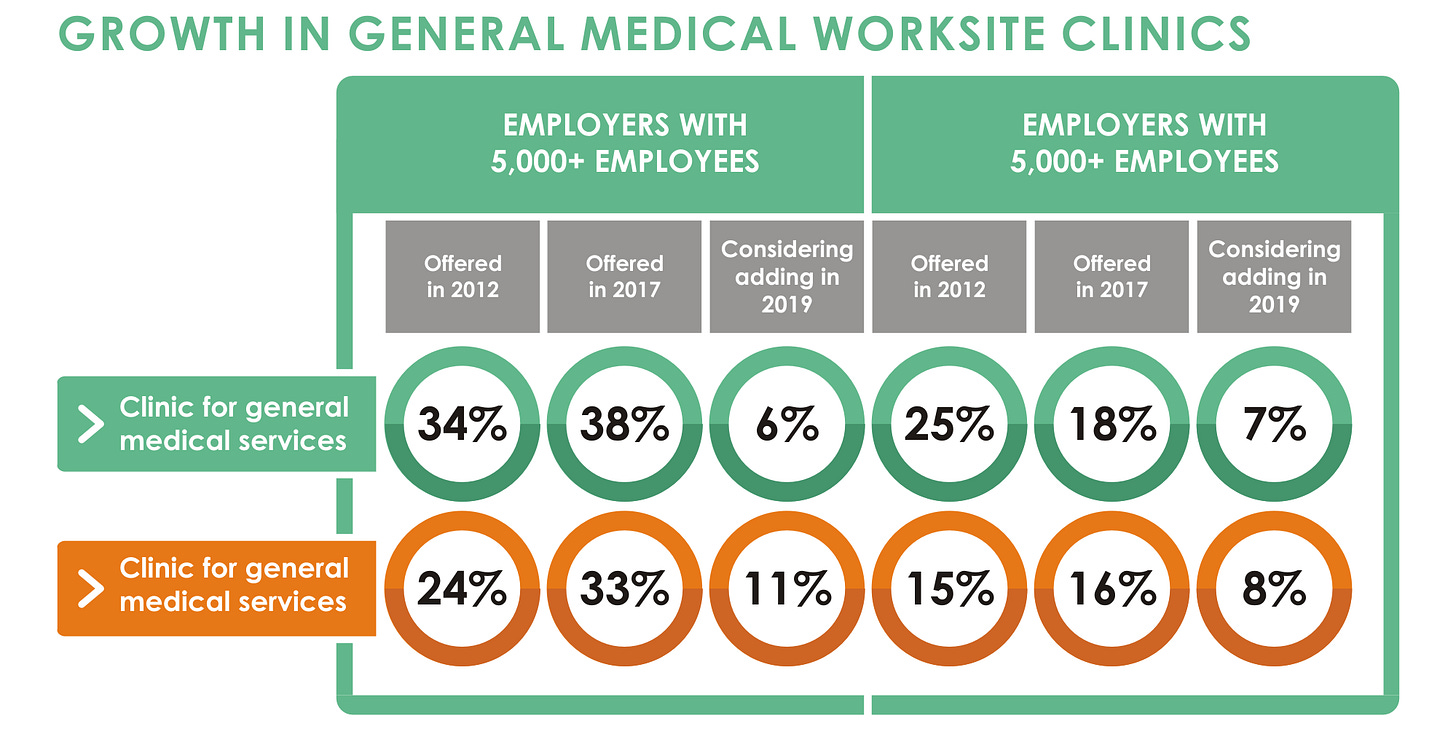

The concept of an onsite clinic isn’t new. Railroad and mining companies first took this approach in the 1860s. If someone broke their arm building something or caught a nasty illness, some professional would be right there to assist. The modern employer’s clinic setup does vary between occupation-specific and general health. It makes sense for people building cutting-edge hardware on an assembly line to have proper medical help available when necessary. According to the patient experience software firm GoShadow, ~1/3rd of companies with >5k employees have general onsite care facilities (up from 24% in 2014). Besides hosting occupational health clinics, such employers are making room for acute care, preventative care, chronic management, and wellness clinics. Separate from traditional medical options, some businesses want to have therapists and nutritionists onsite. The employees now double as patients. Onsite practices serve as a bargaining chip for new hires. Given how tight yet shaky the labor market has become, locking in enhanced medical benefits is compelling to many. For those still going to offices or factories, this is convenient. Firms want the vertical integration and cost savings from having their own medical offices rather than leaning hard on surrounding clinics. Now patients miss less work, save extra time, and find more engagement with the company at large. Workers may not have time or the interest to seek their own doctor from the local pool of public and private clinics. Employers can make that crucial medical coordination step easy. Sounds like a clean win. Yet a few patients might feel this setup is too controlling. Doing work and then getting medical care at the same place could be draining. Cynics may feel that their employer’s doctors might take shortcuts in getting staff back to work as quickly as possible. The incentives are similar to medical staff on a pro football team rushing their quarterback onto the field again after a dreadful concussion or muscle tear from the week prior. Just beware of what you’re trading for convenience of medical care at work.

Big tech’s not the first cohort spending billions on healthcare acquisitions. The UnitedHealth Group conglomerate has been scooping up large and small players for decades. If you look up vertical integration in healthcare, you’ll probably just find the UnitedHealthCare logo. That company directly employs almost 100k physicians while running a massive prescription benefit operation. And of course, their traditional health coverage supports these newer activities. Even during this year, so far, UnitedHealth committed ~$19.2B to buy LHC group ($5.4B announced 3/2022) for home health facilities and Change Healthcare ($13.8B announced 2/2022) for clinic management/payments solutions. So why are businesses and investors alike buying medical clinics with this kind of money lying around? Various players believe they can step into a clinic, turn up the billing, reduce costs, and fund those moves with debt to secure amazing returns. The better question is: do those compounding gains move in sync with patients’ care quality and experiences? The answer in practice is more complicated than the answer in theory.

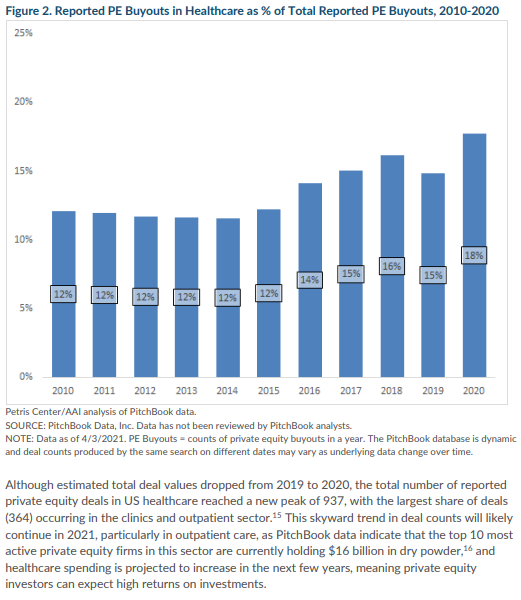

As you’d expect, investors and shareholders would like returns. The market’s going to reward certain holdings more than others. Reality shows us that buying hospitals and certain clinics pays well. UC Berkeley and the American Antitrust Institute wrote a paper covering private equity (PE) healthcare acquisition trends. The authors noted that $41.5B of 352 deals in 2010 grew about 2.3x to $95.9B of 937 deals in 2020. The share of healthcare buyouts in reported private equity transactions overall grew from 12% in 2010 to 18% in 2020 (a 41% increase). Those numbers wouldn’t behave that way if those purchases weren’t profitable. Here’s the play that private equity companies run. Buy some large or many small healthcare facilities with mostly debt financing, consolidate the clinics’ operations under one umbrella, raise earnings though billing and referrals etc., cut costs from unnecessary staff, and sell the whole portfolio with a higher multiple driven by those aforementioned factors. The incentives to pump up returns and improve care for patients clash among multiple areas. Drawing a map to pinpoint all the involved characters is helpful but unnecessary for now. I’ll link UC Berkeley’s more detailed analysis on my page at rushinagalla.susbtack.com. The conflicts start with the purpose of each party.

A hospital is supposed to be around for generations of patients, if possible. Private equity funds and similar investment vehicles have a finite lifetime, targeting about ten years. Investors have to make a return someday, and hospitals aren’t necessarily a multi-generation buy-and-hold move. Hence, earnings need to grow or the valuation of the hospital must expand, both of which have no clear link to patients’ long-term well-being. Healthier patients don’t come back to the hospital often, and not everyone needs repeated surgeries. Non-medical owners want to consolidate their healthcare facility holdings in an effort to organize care, streamline communication among provider teams, and raise bargaining power with insurance companies. These are good things on paper. However, most such investors shift their focus to higher-margin services (like elective procedures), keep crucial staff to the bare minimum, and upgrade only the equipment in true disrepair. Overbilling and internal referral strategies become common as well to bring more revenue at less cost. If all the medical practices in a region condense into just one or a few possible locations to get care, prices for patients and insurance companies would rise as well. A few institutions might do a little something known as “cream-skimming,” which is the act of admitting more profitable patients while barring underinsured patients from care. These approaches let the hospital’s earnings climb long enough to let other investors drag out projections justifying a higher valuation. A raised valuation invites a buyout from another investor. And the cycle continues. Patients moving into a corporate practice worry about the quality of services and staff as well as the accessibility of that expertise. Old admins stress over losing their job. Doctors ask for new equipment and salary with more bonuses but also less red tape. I painted a rather bleak picture just now, but there are happier perspectives for patients to know.

Capitalism in healthcare can work for stakeholders besides investors. A corporation buys an underperforming, lower quality hospital in a reasonable location, replaces staff, improves equipment, modestly raises costs, patients get better care for the amounts they spend, and local authorities may claim some more tax revenue from these businesses. Multiple facts seemingly in conflict can be true all at once. There are policy suggestions to clean up practice acquisition incentives ranging from new FTC guidelines to making certain metrics behind the deals more transparent. Patients themselves can still do a few things to stand their ground. When interacting with any hospital, investor-controlled or not, patients should ask for billing policies and good-faith estimates upfront when possible. It’s also critical to be clear about HIPAA permissions and have a willingness to be referred elsewhere for care when applicable. Take advantage of the right to have a second opinion outside of a given health system as well. Reach out to your health plan before getting care as needed. There’s plenty else to consider here, but these guidelines are a reasonable start.

At this point, I’d normally close out today’s episode with a little preview for the coming week. But for now, I’m mixing things up a bit. I’m going change most of my new posts into shorter videos breaking down each bit of guidance patients need to know. I want healthcare to even more digestible for all patients, readers, and listeners, so I’m going to use short-form content and some lightheartedness to help make that happen. I’ll keep the next few topics a surprise for now. Stay tuned and subscribe to Friendly Neighborhood Patient for every healthcare subject you need to know. I’ll catch you at the next episode!